About White Earth

About White Earth

The White Earth Reservation is located in northwestern Minnesota. The reservation covers 1,300 square miles and includes 3 counties: Mahnomen, Becker, and Clearwater. The White Earth Reservation includes 5 incorporated cities and 5 major villages. The Reservation has 11 communities ranging in size from 50 to 1,200 people within its boundaries. There are 9,188 people living on the White Earth Reservation, of which 4,029 identify themselves as American Indian. The reservation is divided into 3 Districts each with an Elected Representative who governs along with a Tribal Chair and Secretary/Treasurer. The five-person Reservation Business Committee is also referred to as a Tribal Council. White Earth has a high unemployment rate (40%), a high poverty rate (46.5%) and a household median income of ($20,250).

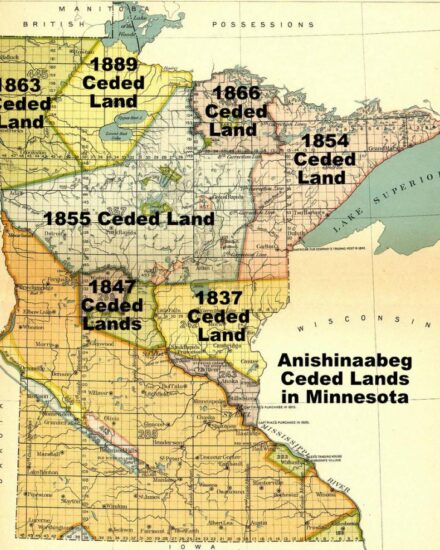

Created in 1867 by a treaty between the United States and the Mississippi Band of Chippewa Indians, it is one of seven Chippewa reservations in Minnesota. Sadly, only 10% of the land base within the reservation boundaries is owned by the White Earth Chippewa Indians. It is checkerboarded, meaning that a land-ownership map of the reservation shows a variety of tribal trust lands, allotted lands owned by one or more individual Indians, and non-Indian fee lands. When lands within a reservation are checkerboarded the jurisdictional analysis will be different for each of the lands. In all circumstances, Indian tribal governments must weave through a complex array of regulatory jurisdictions to determine their authorities to act. Governmental relationships are a constant factor in Indian Country. The complexity of regulatory jurisdiction also makes it difficult to draw outside businesses, industries, or investors to the reservation since they are unable to predict the regulatory environment making any investment too risky.

It is checkerboarded, meaning that a land-ownership map of the reservation shows a variety of tribal trust lands, allotted lands owned by one or more individual Indians, and non-Indian fee lands. When lands within a reservation are checkerboarded the jurisdictional analysis will be different for each of the lands. In all circumstances, Indian tribal governments must weave through a complex array of regulatory jurisdictions to determine their authorities to act. Governmental relationships are a constant factor in Indian Country. The complexity of regulatory jurisdiction also makes it difficult to draw outside businesses, industries, or investors to the reservation since they are unable to predict the regulatory environment making any investment too risky.

The White Earth Reservation Housing Authority oversees 660 low-income rental housing units and 230 turn-key/tax credit units. Many of these units are in dire need of repairs and qualify for condemnation. Families often remain on housing rental lists for years. The consequences of substandard and inadequate housing are severe and long-term, and include chronic disease, physical injury, and other health problems, as well as harmful effects on childhood development.

White Earth has a rich history and a unique socioeconomic profile that stems from Governmental Laws and Policies promoting structural poverty. Since 1867, White Earth has suffered from inefficient energy and housing infrastructure. Systemic change is difficult in and of itself and for all reservations it is nearly impossible to achieve. In its July 2023 addition, Tribal Business News published an article SOLVING THE PUZZLE… HOUSING IN INDAIN COUNTRY reported that “aside from the $50 billion it would take to build enough housing for all American Indians that need it, the most decisive piece of the puzzle is strong tribal leadership.” Tribal housing success begins with a sovereign tribal council declaring a need and supporting homeownership.

It is critical for Tribal Government to change their “Mode of Operation” within its infrastructure to resolve its energy/housing/public health crisis. Yet rather than commit to the difficult task of “systemic change,” tribal governments and housing authorities continued to follow the status quo of hiring the same architects, with the same wasteful designs and the utilization of obsolete construction methods. Their path of least resistance sustains the same deplorable houses being built along with the crippling energy bills our people struggle to pay.

White Earth Housing Problems

Energy Problems in White Earth

Inefficient housing is a key factor leading to high energy burdens. Couple that with the fact three of the four electrical providers that serve the reservation are co-ops that have zero incentive or desire for renewable energy and charge high monthly service fees (currently $50 per month) to all its customers. These co-ops were established by the Federal Government to serve rural areas in the US and are subsidized to do it. Their reconnection fees after shut-offs are shamefully high. It is extremely difficult in an area struggling to generate sustained economic development with expensive electricity that the population cannot afford.

The American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (ACEEE) reports Native American households pay 45% more of their income on energy bills compared to white (non-Hispanic) households and residents of manufactured homes have 71% higher energy burdens. White Earth is inundated with manufactured homes.

Energy inequalities on the White Earth Reservation, like in many other Native American reservations and disadvantaged communities, are shaped by a combination of historical, economic, social, and environmental factors. Some of the key energy-related inequalities on the White Earth Reservation include:

- Lack of Access to Reliable Energy Sources: Some residents on the White Earth Reservation may lack access to reliable and affordable energy sources, including electricity and heating fuels. This can result in difficulties in maintaining comfortable living conditions, particularly during harsh winters.

- Energy Poverty: Energy poverty refers to the condition in which households must spend a disproportionate amount of their income on energy costs. Many households on the reservation may struggle with energy poverty due to limited economic resources and the high cost of energy, including electricity and heating.

- Housing Conditions: The quality of housing on the reservation can vary significantly, and some homes may lack proper insulation, energy-efficient appliances, or access to clean and reliable heating sources. Poor housing conditions can lead to higher energy consumption and costs.

- Limited Access to Renewable Energy: Transitioning to renewable energy sources like solar and wind power can be challenging due to the upfront costs of installation and limited access to financing options. Many residents on the reservation may not have the resources to invest in renewable energy systems.

- Environmental Justice Concerns: The extraction and production of energy resources, such as fossil fuels, can have negative environmental impacts on Native American lands. These activities may disproportionately affect the health and well-being of reservation residents, leading to environmental justice concerns.

- Infrastructure Challenges: Aging or inadequate energy infrastructure can result in power outages, unreliable service, and difficulties in meeting the energy needs of the community. Improving and modernizing infrastructure can be costly and may not always be prioritized.

- Lack of Energy Efficiency Programs: Energy efficiency programs and initiatives can help residents reduce their energy consumption and lower energy bills. The availability of such programs may be limited on the reservation, leaving residents without opportunities to make their homes more energy-efficient.

Efforts to address energy inequalities on the White Earth Reservation often involve a combination of strategies, including improving access to affordable and reliable energy sources, promoting energy efficiency and conservation, and exploring renewable energy options. Partnerships with tribal governments, non-profit organizations, and government agencies can help address these complex issues and work toward a more equitable and sustainable energy future for the community.

Food Insecurity

Food insecurity among Tribal communities today cannot be divorced from their land history, as federal policy promoted settler-colonialism and land theft, which disrupted Tribal communities’ food systems. Euro-American settler colonialism transformed agricultural, hunting, fishing, and gathering practices that had been honed for generations. Although Tribes and Tribal communities adapted and continue to adapt in the face of continued hardships, both access to and production of fresh, healthy food remains a problem on White Earth. It remains a food desert.

White Earth Reservation has many settlements located within its’ 1,300 sq mile border including Beaulieu, Elbow Lake, Midway, Naytahwaush, Pine Bend, Pine Point, Roy Lake, South Roy Lake, South End, The Ranch, Twin Lakes, Bejou, Callaway, Mahnomen, Ogema, and Waubun. There is only one full-service grocery (Mahnomen) store within the entire reservation boundary and nine convenience stores (Callaway, Ogema, Waubun, Mahnomen, Pine Point, Bejou, Roy Lake, Naytahwaush, and White Earth). The stores are not within walking distance for most people and require a vehicle to access them which many people don’t have. The cost and ability to access healthy food are both significant barriers to healthy nutrition.

Currently, there is a lack of access (financial and geographic) to healthy foods and an overabundance of unhealthy “C-Store” food in their communities. There is high need as well as demand for better access to healthy food, traditional Native and affordable food. There is an immense need to create a sustainable and viable food system on the White Earth Reservation. People residing within reservation boundary tend to pay considerably higher prices for food that is not nutritious or healthy.

Food insecurity on the White Earth Indian Reservation, like in many other Native American reservations and disadvantaged communities, is influenced by a complex interplay of social, economic, historical, and environmental factors. Some of the key factors contributing to food insecurity on the White Earth Indian Reservation include:

-

Historical Trauma: The history of colonization, forced removal from ancestral lands, loss of traditional hunting and gathering territories, and cultural disruption have left lasting impacts on Native American communities. These historical traumas have contributed to poverty, limited access to resources, and challenges in maintaining traditional food systems.

-

Poverty and Unemployment: High levels of poverty and unemployment on reservations can limit individuals and families’ ability to afford nutritious food. Limited job opportunities, low wages, and lack of access to education and training programs can perpetuate economic hardships.

-

Limited Access to Healthy Foods: Many reservations are located in remote or rural areas with limited access to grocery stores or markets that offer a variety of fresh and healthy foods. This lack of access can result in a reliance on convenience stores and fast food outlets, which often offer less nutritious options.

-

Health Disparities: Native American communities often experience higher rates of diet-related health conditions, such as obesity and diabetes. These health disparities can further exacerbate food insecurity as individuals may face increased healthcare costs and limited access to nutritious foods.

-

Land and Resource Ownership: Issues related to land ownership, land use rights, and control over natural resources can impact the ability of Native communities to engage in traditional farming, hunting, and gathering practices. These challenges can hinder efforts to regain food sovereignty and self-sufficiency.

-

Policy and Governmental Factors: Federal policies, including those related to land management, resource allocation, and social services, have historically played a role in creating and perpetuating food insecurity among Native American populations. Inadequate funding for programs that address food access and nutrition can also contribute to the problem.

-

Climate and Environmental Challenges: Climate change and environmental degradation can affect the availability of traditional foods, such as fish, game, and edible plants. These changes can disrupt traditional food systems and make it more difficult to rely on subsistence practices.

Efforts to address food insecurity on the White Earth Indian Reservation and other Native American reservations often involve a combination of strategies, including increasing access to healthy foods, supporting traditional food systems, promoting economic development, and advocating for policy changes that empower communities to address their unique food-related challenges. Community-led initiatives and partnerships with tribal governments, non-profit organizations, and government agencies can help address these complex issues.

Health Issues

The forced pressure to shift from a traditional way of life toward a Western lifestyle has dramatically impacted the health and welfare of all Native people and created a terrible epidemic of chronic diseases such as diabetes, heart disease, tuberculosis, and cancer. The statistics identified by Indian Health Disparities are alarming:

- Heart disease is the leading cause of death.

- Due to the link between heart disease, diabetes, poverty, and quality of nutrition and health care, 36% of Natives with heart disease will die before age 65 compared to 15% of Caucasians.

- American Indians are 177% more likely to die from diabetes.

- 500% more likely to die from tuberculosis

- 82% are more likely to die from suicide.

- Cancer rates and disparities related to cancer treatment are higher than for other Americans.

- Infant death rates are 60% higher than for Caucasians.

- During the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, Native Americans faced the highest rates of infection, hospitalization, and death due to COVID-19 when compared with any other race or ethnicity in the United States.

- In Minnesota, American Indians are more likely to die of chronic diseases than other racial/ethnic groups.

- American Indians are also more likely to die of nephritis (kidney disease) than any other racial/ethnic group.

- Health disparities start early for American Indians in Minnesota. American Indian women are seven times more likely than white women (16% versus 2.3%) to receive inadequate care or no care during their pregnancies. Further, the American Indian infant mortality rate is more than double that of the white population.

Food insecurity among Tribal communities today cannot be divorced from their land history, as federal policy promoted settler-colonialism and land theft, which disrupted Tribal communities’ food systems. Euro-American settler colonialism transformed agricultural, hunting, fishing, and gathering practices that had been honed for generations. Although Tribes and Tribal communities adapted and continue to adapt in the face of continued hardships, both access to and production of fresh, healthy food remains a problem on White Earth. It remains a food desert.

Poverty

Poverty on the White Earth Indian Reservation, like in many other Native American reservations, is the result of a complex interplay of historical, economic, social, and environmental factors. Some of the key causes of poverty on the White Earth Reservation include:

- Historical Trauma: The history of colonization, forced removal from ancestral lands, loss of traditional hunting and gathering territories, and cultural disruption have left lasting impacts on Native American communities. These historical traumas have contributed to economic disparities and poverty.

- Limited Economic Opportunities: The lack of job opportunities on the reservation, combined with lower educational attainment and skills training, can result in high unemployment rates and limited income-earning potential for residents.

- Education Disparities: Unequal access to quality education and lower graduation rates among Native American students can limit their future employment prospects and economic mobility.

- Housing Challenges: Inadequate and overcrowded housing conditions are common on many reservations, including White Earth. Poor housing can have a detrimental impact on health and well-being and can make it difficult for families to escape poverty.

- Health Disparities: Higher rates of chronic health conditions, such as diabetes and obesity, among Native American populations can lead to increased healthcare costs and reduced economic stability.

- Lack of Access to Healthcare: Limited access to quality healthcare services, particularly in rural areas, can result in untreated health issues and higher healthcare expenses.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Issues: Substance abuse and mental health challenges can be prevalent on reservations and can hinder individuals’ ability to maintain employment and financial stability.

- Limited Access to Financial Services: Some residents on reservations may have limited access to banking and financial services, making it difficult to save, invest, or access credit.

- Land and Resource Ownership: Issues related to land ownership, land use rights, and control over natural resources can impact economic development opportunities and the ability of Native communities to generate income from their lands.

- Government Policy: Federal policies, both historical and contemporary, have had a significant impact on the economic conditions of Native American reservations. Policies related to land management, resource allocation, and social services funding have often worked to the detriment of these communities.

Efforts to address poverty on the White Earth Indian Reservation often involve a combination of strategies, including economic development initiatives, education and job training programs, healthcare access improvements, housing development, and advocacy for policy changes that empower communities to address their unique challenges. Additionally, community-led initiatives and partnerships with tribal governments, non-profit organizations, and government agencies can help address these complex issues and work toward a more equitable and economically stable future for the community.

Who Are We Working For?

We are a large group of people who powered movement fighting for a green and peaceful future for your land, forest, oceans, foods, climate and pass the green earth to our children. Each one of us can make small changes in our lives, but together we can change the world. Sed posuere consectetur est at lobortis. Duis mollis, est non commodo luctus, nisi erat porttitor ligula, eget lacinia odio sem nec elit. Fusce dapibus, tellus ac cursus commodo.

The only way to make this happen is to make action!

Praesent commodo cursus magna, vel scelerisque nislet.